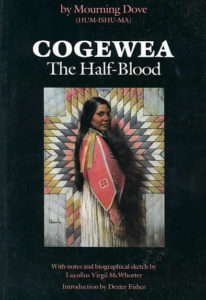

The importance of ethics when undertaking the responsibility of classification cannot be overstated. In considering this responsibility I am reminded of research I did on Native American author, Mourning Dove and her novel Cogewea: The Half Blood. At one point Mourning Dove was considered the first Native American Woman author, however, much of the scholarship revolving around her and her novel is centered on a man named Lucullus McWhorter. McWhorter was an anthropologist interested in Native American culture and history. He met Mourning Dove at a local event and the two developed a correspondence about her writing and McWhorter later became the editor of her novel. However, the two had different ideas about the story her novel would tell. While Mourning Dove had the intentions of writing a “western romance,” McWhorter was intent on selling the novel as a text about the Native American experience. Against her will, McWhorter pushed an “authentic looking” Native American depiction of Mourning Dove on the cover, added epitaphs before each chapter, and more. In all my research on the text , I would say the most frequently cited quote is Mourning Dove’s statement in a letter to McWhorter:

“I felt like it was some one else’s book and not mine at all. In fact, the finishing touches are put there by you, and I have never seen it.”

Some critics believe that McWhorter’s role in the processing, packaging and even the content of Mourning Dove’s novel was so large that Mourning Dove’s authorship is invalidated. What is most upsetting is not that McWhorter’s agenda is so apparent in Mourning Dove’s novel but is that Mourning Dove’s text has not received the critical attention it deserves or reached the audience it intended because the discourse is so focused on McWhorter. McWhorter injected himself into Mourning Dove’s text and to this day that is the only narrative in circulation.

I have included this story because it is a cautionary tale of what not to do. While McWhorter’s role was editor and not someone who implemented a digital classification system, one can read his choice of picture on the cover of the text as a title, and his epitaph’s as a form of metadata. In fact, it is important to note that McWhorter, as an anthropologist, most likely had a scholarly audience in mind, as opposed to Mourning Dove, who was interested in writing a western romance. Thus, As students working with metadata for documents and materials pertaining to the Watts Rebellion, it is impossible to know the full story behind each document, but it is our responsibility to not only make these documents available via the most ethical classification system but also, in doing so, to honor the history of the community and the requests of the Southern California Library.

One of the most challenging parts of this project will be keeping audience in mind. In order for this to be done ethically, these materials must be accessible to both scholarly researchers and members of the community. One way I can imagine functioning is by balancing tags and metadata heavy with academic or governmental jargon with appropriate synonyms. The other challenging aspect will be representing the materials accurately. My answer to the question of whether or not we can represent these materials accurately is: I’m not sure. As an academic I want to be an extremely well researched on a topic before I make any public claims about it. Thus, my inclination in representing these materials via metadata and tagging is to approach it like I would writing a seminar paper: research, research research. However, becoming an expert on each document is simply not possible given the reasonable time constraints, yet, this is an issue I still struggle with.

A question I am left with is this: When it comes to metadata and tagging, is it better to take a minimalist approach or to include a large amount of metadata, which risks creating a narrative for an object before a user has read the material themselves?